Strategic Alignment and Access

Governance

By André Koot

© 2022 IDPro, André Koot

To comment on this article, please visit our GitHub repository and submit an issue .

Introduction

Many Information Technology (IT) departments are responsible for implementing IAM systems to support an organization’s efforts to operate efficiently and effectively. Identity management systems are designed to automate the joiner, mover, and leaver processes (JML processes) for employees. 1 Access management systems, in turn, are designed to make it possible to request and grant authorizations in information systems and even physical access to facilities such as buildings or data centers. For IT to support the necessary processes and controls, they must understand the business drivers for the organization. IT in general, and IAM in particular, must serve the organization; strategic alignment is critically important and, unfortunately, challenging. Different day-to-day languages, cultures, and priorities obstruct the understanding on both sides regarding what has to happen and why for the business to succeed.

Terminology

-

Alignment: the synchronization rate of processes and environments

-

Governance: making sure that accountable owners are demonstrably in control

-

Identity Governance and Administration: a solution for automating user management and authorizations in target systems, building on the organization’s customer and human resource processes.

-

Joiner-Mover-Leaver processes: The joiner/mover/leaver lifecycle of an employee identity considers three stages in the life cycle: joining the organization, moving within the organization, and leaving the organization.

Acronyms

-

CEO: Chief Executive Officer; CFO Chief Financial Officer; CRO Chief Risk Officer; CTO Chief Technology Officer; COO: Chief Operations Officer

-

RBAC: Role-Based Access Control

-

IGA: Identity Governance and Administration

-

JML processes: joiner, mover, and leaver processes

Understanding Strategic Alignment

Business-to-IT Alignment, also known as Strategic Alignment, has been studied since the 1980s. Following the Henderson and Venkatraman model, strategic alignment brings together a dynamic integration of IT planning and business development to shape or enable a holistic business strategy. 2

Ideally, IT enables the business to perform efficiently and effectively. IT can help solve business issues by providing logical, structured ways of working, integrating solutions, and making access and application integrations possible. For example, IT supports automating manual tasks, keeping records, integrating different information processing components and systems, and following security best practices. IT better understands what problems need to be solved when aligned closely with the organization’s business drivers. In general, businesses are more successful when they incorporate the efficiencies IT can bring to the table.

In order to reach the necessary levels of strategic alignment, we first must consider the barriers. Often, the language used by the business to identify what’s important is quite different than the language used in IT.

| Business talks about | IT talks about | |

| Customer satisfaction | System service level agreements (e.g., 99.999% availability) | |

| Return on Investment (ROI) | Network architecture (e.g., hybrid, cloud, on-prem) | |

| Legal and regulatory requirements (e.g., GDPR, CCPA) | Common Vulnerability and Exposure (CVE) Announcements 3 | |

| Market share | Latest container management technologies (e.g., Kubernetes) | |

| Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) | Access control mechanics (e.g., -rwxr-xr-x) | |

| Financial bottom line (i.e., General ledger) | Network capabilities (e.g., bits per second, database structures)BPS | |

| Interest rates | Data Center architecture and computing clusters | |

| Consumer trust and business reputation | P1 (Priority 1 incidents) |

(There is no implied horizontal correlation between the terms in the left and right columns).

Alignment Models

There are different methodologies that describe the necessary points of communication to support strategic alignment. Hendersen and Venkatraman, two IBM fellows, came up with this model for strategic alignment in 1993: 4

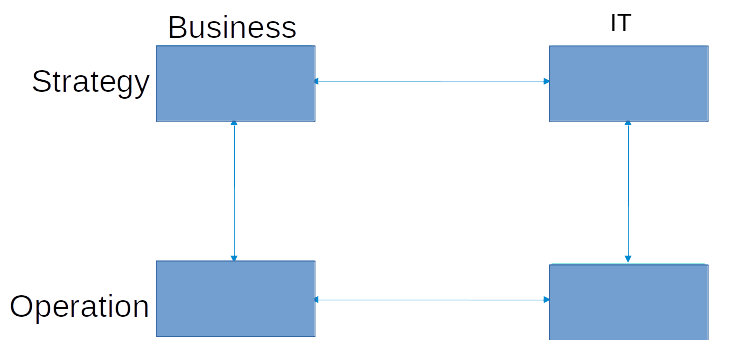

Figure 1: Simple Model for Strategic Alignment

This model suggests that business and IT stakeholders should communicate on both the strategic and the operational levels. This multidirectional communication ensures that the business processes are supported by fitting IT solutions. By pairing strategic choices with operational ones, the organization can minimize unnecessary changes in process and technology. For this model to work, however, the organization must address the fact that IT and the business often have different ways of working, cultures, languages, and jargon. These differences make strategic alignment difficult.

One critical characteristic of this model (and in the other models presented) is that communication between domains/cells can only occur across the horizontal and vertical lines, not diagonally. That means communication can only happen in formalized relations to prevent disrupting formal, mature procedures.

Case CEO:

My old CEO was tempted to get a smartphone. All young marketers used those devices, so why not the CEO? But he also wanted to read his company email on the same smartphone. This expectation would not be a problem except for the fact that in 2008 enterprises were not supporting those devices in a standard way. The CEO directly ordered an IT engineer to make it possible: install the app, connect to the mail server, create a secure channel to the Internet, add certificates, etc. This non-standard change interrupted IT operations for three months.

In the Amsterdam Information Model by Professor Rik Maes, Dr. Maes added additional components to implement information management and structure. 5 :

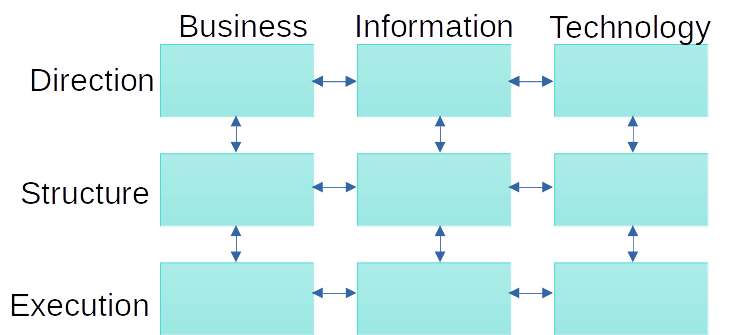

Figure 2: the Amsterdam Information Model for Strategic Alignment

The middle column, Information management, translates the business requirements into IT solutions (left-to-right translation). It also translates the features and functionality of IT components (platforms, services, applications) into business opportunities (the right-to-left translation). The information management function must overcome the issues indicated above, such as language and cultural differences. The information manager (or CIO) should understand and know how to converse with businesspeople and IT personnel. The information manager should be able to connect to the entire organization and act as the missing link in business-to-IT alignment.

The added horizontal middle layer also has a specific ‘translation’ role:

This layer can be seen as the architecture layer. It translates strategic concepts into day-to-day operations. Looking at the different columns within this layer, from left to right, we can identify the following architectural concepts:

-

Business architecture (organogram/org-chart and business processes models, including Segregation of Duties (SoD), abuse of information prevention controls, etc.).

-

Information architecture (data models, -flows, and interfaces).

-

The IT architecture (including servers and networking, containerization, cloud, and security architecture).

In this model, we can position the CEO, CFO, and COO in the top-left area. These persons are accountable for defining the organization's business strategy, direction, and course. The head of IT, or CTO (Chief Technology Officer), would be positioned in the top-right area, accountable for IT strategy, like sourcing strategy and IT vendor management strategy. This assignment leaves the CIO in control of the middle column, responsible for the business-to-IT alignment.

Governance, ownership of control, would, in this model, be owned by the top-left area players.

IAM and Alignment

So far in this article, we have focused on the IT/business relationship in general. As IAM is traditionally considered part of IT, the challenges of strategic alignment are at the core of most failures of IAM projects. In many cases, IAM is very much an IT function. IAM includes basic “techie” tasks such as password resets, account management, user provisioning, and so on. IAM, however, is arguably more closely tied to business needs than any other aspect of IT. Authorization processes, in particular, regularly bridge the gap between IT operations and business requirements.

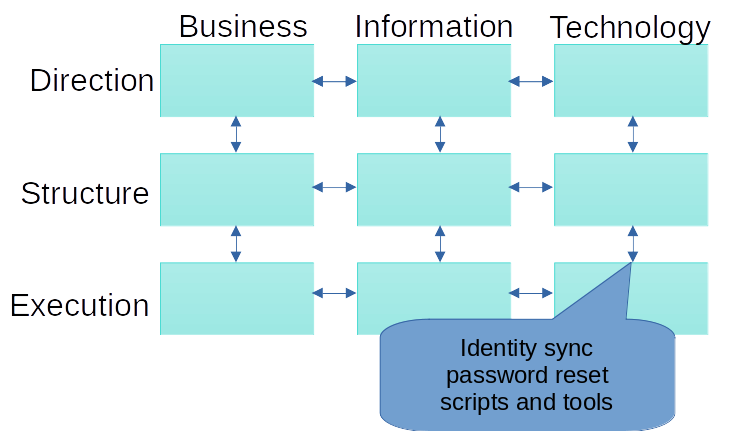

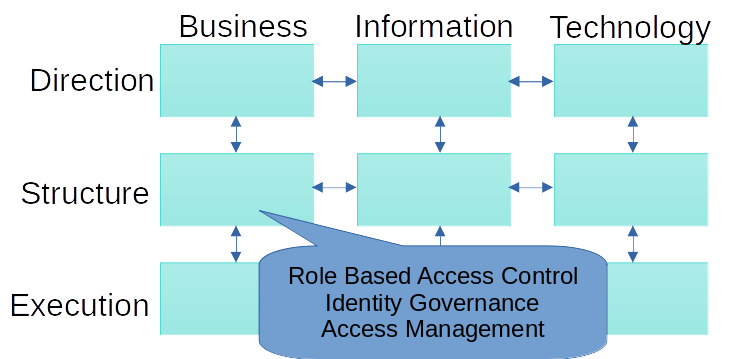

Figure 3: Amsterdam Information Model - IAM as an IT Function

IAM started as an IT responsibility. Creating interfaces and connectors, protocols, and adding certificates all fell in the realm of IAM and IT. The trigger for all identity transactions was often the HR department, but in daily operations, identity management belonged to IT as part of the general task of automating business processes. That has not changed. Most identity management in an organization is still seen as IT: bottom right.

Authorization management, on the other hand, is not as easily plotted. Authorization involves “determining a user’s rights to access functionality with a computer application and the level at which that access should be granted. In most cases, an ‘authority’ defines and grants access, but in some cases, access is granted because of inherent rights (like patient access to their own medical data).” 6 Authorization is directly tied to business practices, and yet the IAM group generally implements them.

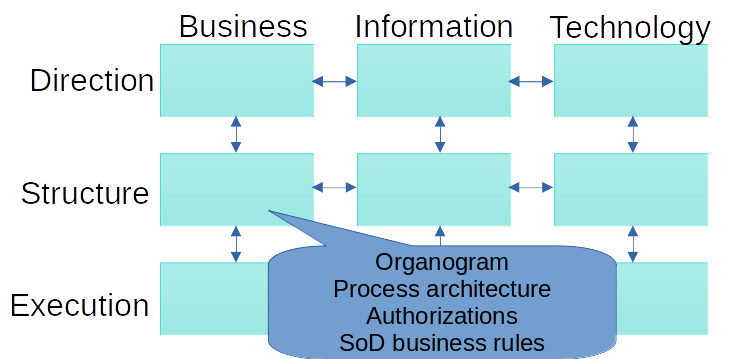

Using the Amsterdam Information Model , we can identify where authorizations are most prominently defined. Authorizations are enablers for performing tasks in an organization and so are critical to the execution phases. Authorizations are derived from the organizational structure and business processes. Implementing authorization management must therefore be plotted on the Business Structure area in the model. For example, SoD rules are defined in a business process: one person may not be allowed to perform multiple successive tasks because that could create a risk of fraud, abuse of permissions, or data breaches. Tasks are defined in a process. That means a process owner, ‘mid-left,’ is accountable for defining these specific access control policies.

Figure 4: Amsterdam Information Model - Authorization as a Business Function

IT does not own or manage business structure authorizations. It’s the responsibility of the ‘business’ owners, specifically the process owners, line managers, or data owners.

Managing authorizations–defining, granting, and revoking them–is one of the more challenging tasks for any organization. This task is where the concept of RBAC became handy. The concept was created in the mainframe era in solutions like IBM’s Resource Access Control Facility (RACF) and the Access Control Facility 2 (ACF2) system. In the local area networking era, RBAC became the solution for managing this authorization complexity. In the nineties, dedicated identity management solutions started to appear, with authorization solutions exploring the concept of RBAC coming into existence at the turn of the century. These solutions evolved over time, eventually offering identity governance by adding attestation/recertification processes.

Figure 5: Amsterdam Information Model - RBAC and Identity Governance

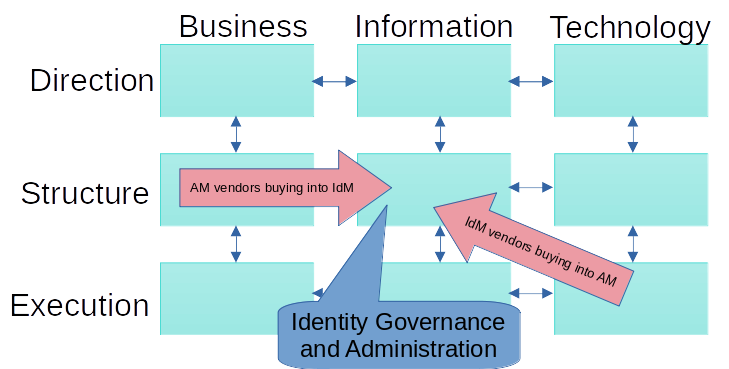

These days, we see vendors moving to a spot in the center. Traditional Identity Management software vendors add authorization management solutions and traditional identity governance vendors add identity and workflow management capabilities. There are also ‘new’ entrants in the market, offering cloud-based solutions such as Identity Governance and Administration offerings.

Figure 6: Amsterdam Information Model - IGA

When evaluating Attribute Based Access Control and Policy Based Access Control models, the same strategic alignment change of responsibility can be seen. Several IT-oriented access control policies exist, such as the requirement to use TLS certificates and zero-trust networking. But other access policies are business oriented. Policies like SoD or privacy-related consent management have a clear relation to the business structure sector in the model.

An Extended Case Study

Information systems were generally developed to support the identity management process and to support authorization management; the current generation of IGA solutions performs their role admirably by supporting the business with reliable identities (based on the HR identity lifecycle) with reliable authorizations. And yet, there still is the issue, IAM is still seen as an IT responsibility. Let me explain this in a case:

Case Study - Accountability vs. Responsibility

A financial institution supports its identity governance and RBAC requirements by using a modern IGA solution. The system is integrated within the IT landscape and connects several business applications for provisioning and reconciliation.

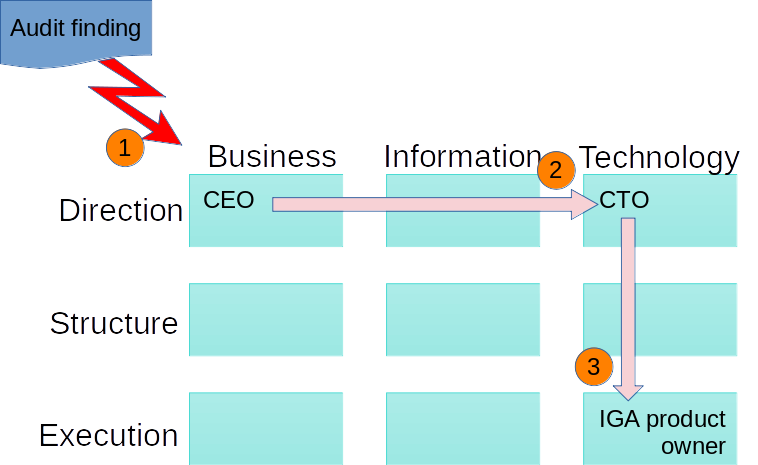

An external auditor reported a high-risk issue concerning authorizations in the financial accounting system to the CEO.

The CEO (Top-left) forwarded the findings to the CTO (Top-right), as the finding was about a system, and so the CEO believed IT had to solve the issue. The CTO forwarded the finding about the authorizations to the IGA product owner in the IT Service delivery department (Bottom-right). Unfortunately, the product owner cannot solve the issue.

What went wrong?

Figure 7: Amsterdam Information Model - default IAM communication

The product owner is responsible for the IGA system but not for the authorization decisions themselves; the product owner cannot fix the issues found by the auditor. In short, the product owner is responsible but not accountable for authorizations. Instead, the process owner for the financial business process should be tasked with resolving the issue.

Note that, based on the Amsterdam Information Model, there is no direct communication between the IGA product owner, who works at the operational level within IT (bottom-right), and the business process owner (center-left) in the business architecture layer. That communication would be a diagonal link and would interfere with regular, well-structured operations.

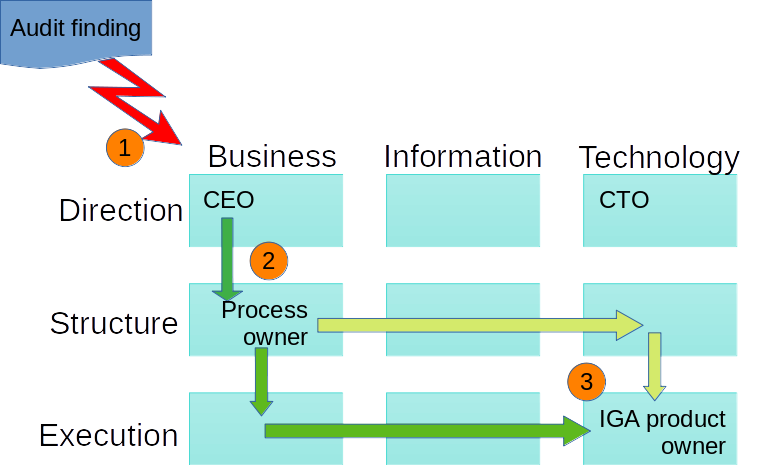

The advice was for the product owner to escalate back vertically to the CTO on the basis of lacking accountability. The CTO should then advise the CEO to assign the issue to a business process owner:

Figure 8: Amsterdam Information Model - Correct Communications Path

(Different paths for the necessary communication could be followed to make the required adaptations to the authorization model in the IGA system.)

The Way Forward

How do these models solve the issue of lack of stakeholdership in organizations? Does the alignment strategy solve the governance challenge?

First and foremost, the theory can demonstrate that access control, or authorization management, is not an IT responsibility. The ‘business’ is accountable for structuring and implementing authorization models and authorization management. IT can, at best, only support the business by implementing the tools that might help.

This makes the implementation of IAM a new challenge. Implementation is not just an IT project. Implementing an identity management solution can be done in an IT project style, but authorization management is not a project. Authorization management is the never-ending responsibility of managers and (business) owners.

And that leads to this conclusion: An IAM project cannot exist as an IT project. Implementing authorization management results in or requires organizational change and is therefore related to regular governance and control of business responsibilities.

Access Governance is what connects the business governance and control challenge to the IT solutions that are used to enable the organization to execute its mission. The easiest way to activate the business is to find someone who makes a decision on the topic of SoD or find someone who is a stakeholder in the approval process for access requests.

Case Study: SoD rules

A financial institution is using a modern IGA solution to manage accounts and authorizations in Active Directory and miscellaneous information systems. This system depends on the concept of SoD. Using the SoD controls, it is impossible to assign two or more conflicting roles to the same employee. There are over 1200 SoD rules in the IGA system.

When asked who had defined those SoD rules, the product owner in the IT department had no idea. While the product owner is responsible for making sure the system runs as expected, holding them accountable for the SoD rules is outside their area of responsibility; they may not even know all the parties involved in making those decisions.

In an ideal world, the SoD rules would not be applied without an accountable business owner clearly identified. In this case, the financial institution has a large business project ahead of them to ensure the appropriate process owners have reviewed each rule.

A good practice would be only to create roles and (business) rules if a person in the business domain can be assigned as the accountable stakeholder for the role or rule. Governance is not just relying on IT departments to solve issues but having someone accountable for managing the business and implementing the controls to manage the business.

Conclusion

In today’s digital age, for an organization to succeed, it must have a strong IT function. That IT function will not be at its best, however, if it is missing a close partnership with the business components of the organization. The different parts must pull in the same direction to succeed.

IAM projects can only succeed with a strong business-to-IT alignment. As evidenced by the challenges associated with the organization-wide responsibilities around authorization management, IAM, perhaps more than any other IT-related function, must understand the needs of the business and enable those requirements in the identity systems.

Both parties are responsible for ensuring strategic alignment across the organization, being aware of and working to overcome the barriers of different cultures and jargon in each group.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank IDPro Principal Editor Heather Flanagan for turning the original, hardly English language, text fragments into readable text.

Author Bio

André Koot is Principal Consultant at SonicBee in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. He is a member of the BoK committee of IDPro.

André Koot is Principal Consultant at SonicBee in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. He is a member of the BoK committee of IDPro.

André has over 30 years of experience in information security and over 20 years of experience in Identity and Access Management. He has a background in financial accountancy and business economics.

-

Cameron, A. & Grewe, O., (2022) “An Overview of the Digital Identity Lifecycle (v2)”, IDPro Body of Knowledge 1(7). doi: https://doi.org/10.55621/idpro.31 ↩

-

Bago (Editor), E. & Glazer, I., (2021) “Introduction to Identity - Part 1: Admin-time (v2)”, IDPro Body of Knowledge 1(7). doi: https://doi.org/10.55621/idpro.27 ↩

-

Henderson, John C., and N. Venkatraman. "Strategic alignment: a process model for integrating information technology and business strategies." (1989), https://dspace.mit.edu/bitstream/handle/1721.1/49138/strategicalignme1989hend.pdf , and Dampney, C. N. G., & Andrews, T. B. (1989). Striving for sustained competitive advantage: the growing alignment of information systems and business. CSIRO Australia Division of Information Technology. ↩

-

Strategic alignment, Henderson and Venkatraman, 1993, reprint at

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-Henderson-and-Venkatraman-strategic-alignment-model-Reprinted-from-Henderson-JC_fig2_220220710 ↩

-

Amsterdam Information Model, 1999, reprint at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242321998_A_Generic_Framework_for_Information_Management ↩

-

Flanagan (Editor), H., (2022) “Terminology in the IDPro Body of Knowledge”, IDPro Body of Knowledge 1(9). doi: https://doi.org/10.55621/idpro.41 . ↩