Introduction to Privileged Access Management (v2)

© 2024 IDPro, André Koot (SonicBee)

To comment on this article, please visit our GitHub repository and submit an issue.

Introduction to Privileged Access

Privileged Access Management (PAM) plays a crucial role in modern cybersecurity. All organizations (at least those with technical infrastructure) maintain accounts with some form of super-user permissions, e.g., the Administrator account on a laptop. Organizations enhance their security posture and protect valuable assets from inside and outside threats by addressing the issues and risks associated with privileged accounts. This requires a combination of robust policies, technologies, and best practices that help organizations manage the risks while ensuring the confidentiality, integrity, and availability (the “CIA Triad”) of systems and data.

Terminology

| Access | The permissions, privileges, and abilities granted to users, account types, system processes, applications, or any other entities within a computing environment. |

| Privileged Access | Users or accounts with high-risk permissions, such as those that grant them access to (critical) systems, sensitive data, and configuration settings |

| Privileged Access Management | A mechanism for managing temporary access for accounts with high-risk permissions. PAM often involves check-out and check-in of a credential generated for a single use. 1 |

| Privileged Account Management | Focuses on special control for risky high-level access. Privileged Account Management (PAM) is a mechanism for getting those special accounts under control.2 |

| Role Based Access Control (RBAC) | The use of roles at runtime: a way to govern who gets access to what through the use of business roles and application roles |

| Joiner/Mover/Leaver | The joiner/mover/leaver lifecycle of an employee identity considers three stages in the life cycle: joining the organization, moving within the organization, and leaving the organization. |

| Least Privilege | The principle that a security architecture should be designed so that each entity is granted the minimum system resources and authorizations that the entity needs to perform its function. 3 |

| Identity Governance and Administration | A discipline that focuses on identity life cycle management and access control from an administrative perspective. 4 |

Acronyms in Use

| CIA: Confidentiality, Integrity, and Availability | The “triad” that forms the basis of information security. |

| RPA: Robotic Process Automation | Autonomous IT solution to automate manual tasks. This autonomy is in contrast to a user-initiated macro. |

| ICS: Industrial Control Systems | Implemented to separate IT environments from Operational Technology environments (e.g., in industrial process industries) |

| SCADA: Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition | An architecture framework to secure ICS environments |

Privileged Accounts

Privileged accounts, often called ‘super-user’ or ‘administrator’ accounts, possess elevated permissions granting access to (critical) systems, sensitive data, and configuration settings. With this level of access, these accounts define the behavior of the component they belong to. ‘Administrator’ is the built-in account needed to configure a Windows component, such as the directory, the filesystem, and the networking capabilities. Similarly, ‘root’ is the super-user account on UNIX and Linux systems and many infrastructure components. In database management systems, there are ‘SA’ (system admin), ‘DBO/DBA’ (database owner/admin), ‘root,’ or ‘postgres.’ These accounts function on behalf of a component itself (rather than a user). Anyone who knows the password can log in and effectively be the component: they can change the component's behavior and thus make or break the system. These super accounts are almighty.

Managing access to privileged accounts should be one of the most common early initiatives in an organization’s identity & access management (IAM) journey. Why? The simple answer is that the organization should manage access where risk is highest. For more detail, look no further than the #1 item in the 2021 OWASP top 10 list of Web Application Security Risks: Broken Access Control (OWASP link).5 Without effective privileged access management (PAM), all three legs of the information security CIA triad can be compromised, sometimes with catastrophic results. This is why, although they vary by country, emerging regulatory frameworks specifically call for controls on privileged access. For example, here is one clause in which the European NIS2 Directive specifically refers to PAM as an essential part of ‘cyber hygiene:’

…Cyber hygiene policies comprising a common baseline set of practices, including software and hardware updates, password changes, the management of new installs, the limitation of administrator-level access accounts, and the backing-up of data, enable a proactive framework of preparedness and overall safety and security in the event of incidents or cyber threats6

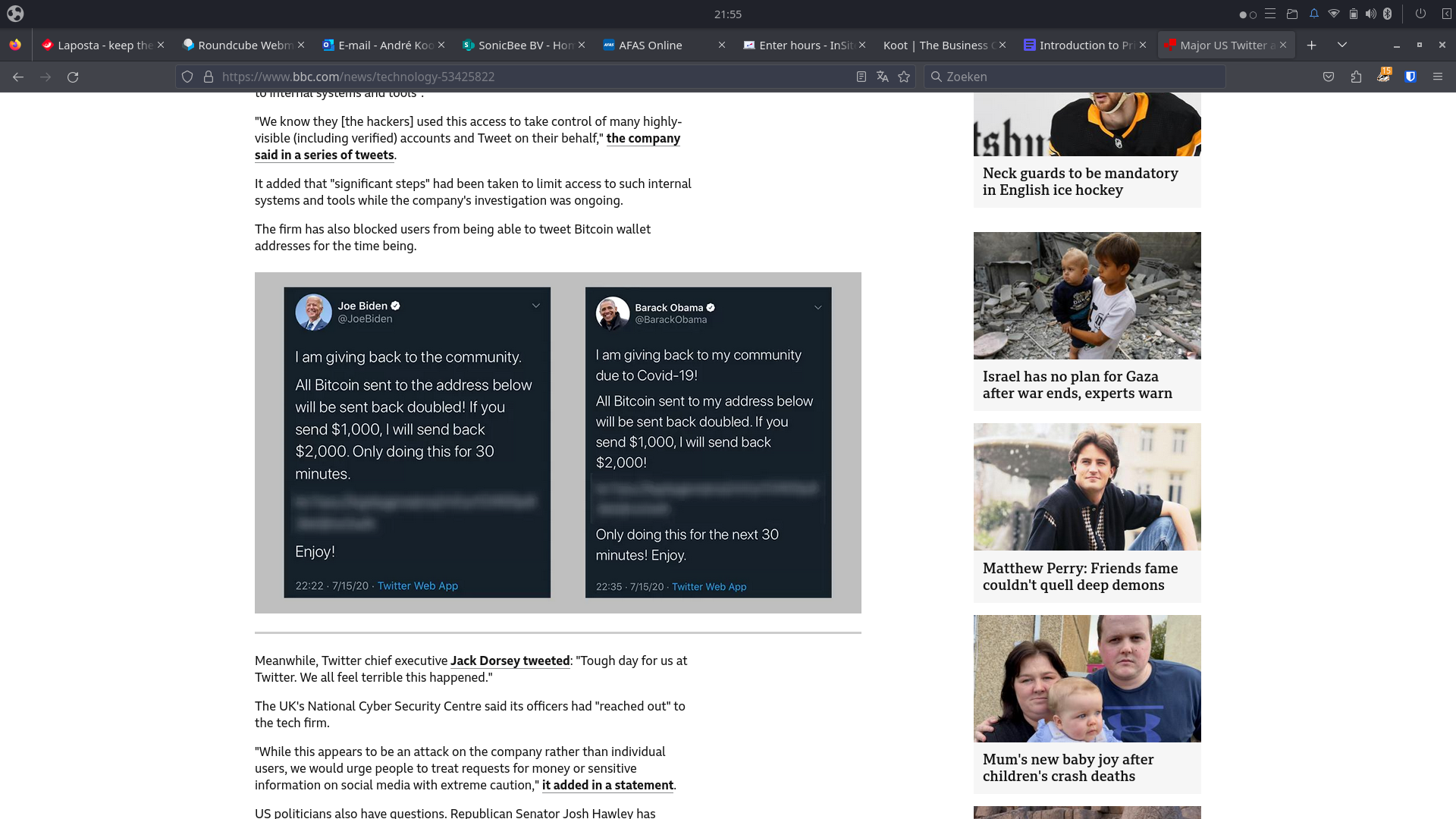

Regulation is not the only reason to start a PAM program. Even if an organization isn’t subject to these compliance controls, managing access to privileged accounts is in its best interests. Figure 1 demonstrates what can happen when unauthorized users gain access to admin accounts.

Figure : In 2020, the admin accounts of Twitter Operations Management software were leaked to a Slack channel and accessed by an unauthorized person, leading to fraudulent activity. 7

Threats of Privileged Access

As demonstrated by the example in Figure 1, organizations that do not constrain the proliferation of – and access to - privileged accounts face several issues. Those issues include:

Over-Privilege: Employees with privileged access might be granted excessive permissions beyond their role requirements, thus increasing the risk of unauthorized actions and data breaches. For example, a support technician who gains full root access when they have a limited or occasional need to restart a single service.

Credential Sharing: When multiple individuals share privileged credentials, organizations may struggle to track who accessed what resources, increasing the chance of a security breach. This creates a lack of accountability. For example, a support team may all know root credentials – a situation exacerbated by employee turnover if those credentials are not changed.

Credential Theft: Cybercriminals often target privileged accounts due to the extensive access they provide. Malicious actors can gain unauthorized access to critical systems and data if these credentials are compromised.

Insider Threats: Trusted employees can become insider threats if their privileged access is misused intentionally or unintentionally.

A Typology of Privileged Access Accounts

Understanding the different types and characteristics of privileged accounts is essential to management and risk mitigation.

Human Privileged Accounts

Generally, human-privileged accounts are governed by the human resource practices in an organization. The CEO, for example, often has more privileges in systems than interns. Because the CEO’s user accounts have more power – and because the CEO is often easily identifiable – their privileged accounts are at a greater risk of attack. Fortunately, executives seldom have root access to Linux servers and are rarely assigned as admins to Windows Server management. However, their access and associated risks should be managed thoughtfully. Role-Based and Policy-Based Access Control can help control the amount of access that such users have.

Another type of access would be individual/nominative accounts – those with root access, global admin rights, or other highly privileged group membership. Managers should consider these accounts high-risk. The usage of these authorizations may not be anonymous, but they should never be assigned for an indefinite amount of time. Just-in-Time (JIT) provisioning or dynamic access controls offer further controls to prevent long-standing high-risk authorizations.

Privileged access may also refer to operations involving sensitive data, e.g., the amount or type of personally identifiable information (PII) or company financial data that an individual user has access to. In some scenarios, privileged access may extend to which customers’ data. For instance, a healthcare organization treating a ‘VIP’ may consider their data more sensitive. While policy and regulation treat them as equal, the collateral damage in the event of a data breach may be more significant, and, therefore, an organization may put more access controls in place.

The key risks applicable to human accounts are two-fold:

Legitimate users (employees, contractors, etc.) gain more access than they should and, thus, put the organization at greater risk of insider threat or data loss.

Bad actors gain access to legitimate users’ accounts through one of many attack vectors, like password spray attacks, phishing campaigns, or consent hacking.

Of course, these risks often work hand-in-hand since bad actors that gain access to the highly-privileged accounts of legitimate users can inflict greater damage.

Best practices for managing this type of account include:

Role-Based and Policy-Based Access Control (RBAC): Authorizations are granted to personnel via business roles.

Multi-factor authentication (MFA): Mandatory MFA dramatically de-risks account take-over.

Least Privilege: Accounts are provisioned with the minimum number of authorizations required to do the job.

Just-in-Time Provisioning: Accounts are authorized only as and when a task needs to be performed. Once a task is finished, the authorizations should be deprovisioned.

Strong Governance: Robust IGA procedures, like access request management and approval workflows, ensure that interventions like RBAC, Least Privilege, and MFA continue functioning.

These controls depend on solid governance and access management processes. For more information on Workforce Identity and Access Management (also called Identity Governance and Administration, or IGA) solutions that support Joiner-Mover-Leaver workflows and Role Based Access Control, see An Overview of the Digital Identity Lifecycle.8 These solutions can, however, not ideal for the management of non-human privileged accounts since the managing process is not a joiner-mover-leaver process.

Non-Human Privileged Accounts

Non-Human Accounts require different management processes and risk mitigation strategies because they are not human (as suggested by the name). These non-human accounts are not managed via a joiner-mover-leaver processes. Instead, events in their lifecycle - which resemble those of human accounts - are triggered by a change management process.

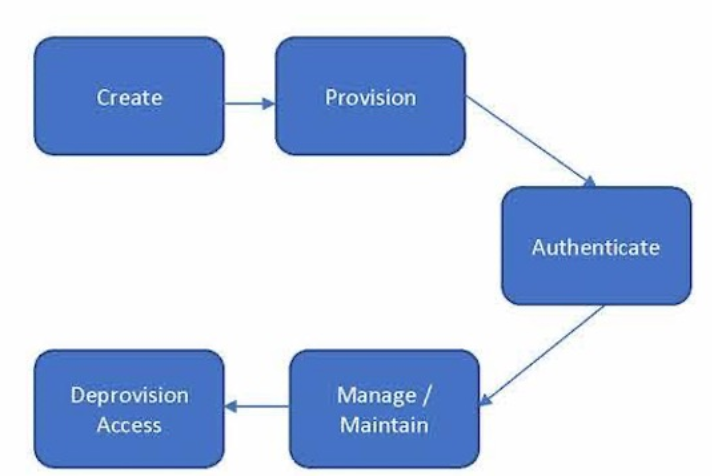

Figure : Lifecycle of Non-Human Accounts

Figure 2 articulates the following lifecycle for non-human accounts:

Create: A non-human account is created as the result of a change request, either in a development process or brought in through a procurement process (rather than an HR process that triggers a human account). The account can belong to a server, a network component, or an RPA.

Provision: The component is activated, gets an identity and an account, and is given the least privileged authorizations required to perform the configured tasks. A secret is configured to make it possible to identify and authenticate the component at runtime.

Authenticate: Once activated, the component needs to be identified by a governing body (like the network) and authenticated, whether by a configured password, a certificate, or a token.

Manage/Maintain: During the lifecycle, the component's functionality can change, and any changes to required authorizations will be managed through the change management process.

Deprovision Access: When the component is decommissioned, access is removed to prevent abuse (practitioners often forget this step).

There are two forms of non-human privileged accounts: those that humans interact with and those they do not. While the main focus of this article is interactive non-human accounts, it is crucial to consider the PAM implications of those that do not interact.

Non-Human, Non-Interactive Privileged Accounts

Some privileged accounts are non-interactive, meaning that humans generally do not log into them to perform business activities. These are the accounts of components like middleware services, such as databases or web servers. These services access resources after a login with a secret kept in a config file using tokens or secrets. These accounts act as placeholders in the system log that register resource usage.

For example, in accounting software, an application may need to register transactions in a relational database. To do this registration, the application looks up the password of the configured service account and logs in to the database. This results in each transaction being logged against and owned by that application. The application must, of course, ensure that the account of every actor is registered as the initiator of their transactions.

Other examples include accounts used for automation, such as batch accounts, macros, or RPAs. The organization’s Technology team documents a change request with the process requirements for each automated task and then creates the appropriate script or configuration to execute the steps. The process itself needs to have the requisite authorization to run. Or, in other words, achieve the minimal required authorizations according to the ‘least privilege’ principle.

In these scenarios, the change requester or requirements owner should be considered the accountable party for the script, macro, or RPA.

Best practices for managing this type of account include:

Change Management Governance: These accounts don’t follow regular IGA processes like JML, and authorizations are not role-based but specific. Ensure an accountable party oversees the requirements and a robust process managing any change to the functionality and authorizations of the component.

Least Privilege: Accounts are provisioned with the minimum number of authorizations required to do the task.

No Login: Make sure that these accounts cannot be logged into in the underlying infrastructure, like the operating system.

To learn more about managing these types of privileged accounts, see Non-human Account Management in the BoK.9

Interactive Non-Human Privileged Accounts

Interactive non-human accounts - the main focus for the remainder of this article - are also called system accounts: these are the built-in component accounts, such as ‘admin’ or ‘root.’ These can also be accounts that are built-in into applications, such as the super-user of an application. A person who needs to use the power of this account will log in to the component with this account name and the password provided by the developer or the vendor. In the session that results, the person is the component.

The existence of these almighty accounts creates severe risks of unauthorized access by individuals capable of breaking or exploiting the component: they can be tremendously damaging to an organization’s security posture if practitioners do not contain and strictly control their usage. As stated, someone who logs in with the component account is the component. And that means that the component itself is the actor, performing all the tasks. Without additional measures, the actual human being may not be known or identifiable.

This type of account should only be used in specific circumstances and for a particular purpose, like during an incident or to deliver a change. This practice is a fundamental security principle. A common control is to raise a ticket in a service management solution when access to this type of account is required. A PAM solution can then check that the ticket is valid. Connecting a PAM solution to the service management solution is best practice.

Best practices for managing this type of account include:

No Default Passwords: Immediately change the default password to prevent unauthorized persons from becoming the component and taking action.

Password Vault: Use a vault to retrieve a password.

Restricted Use: If possible, these accounts should only be used once during setup and then deactivated (if possible) or heavily restricted (e.g., for disaster recovery scenarios).

Named Super-Users: Ensure that usage of the super-user account can be traced to a person. For example, on Linux systems, a system operator logs in normally under their own credential and then uses sudo to promote to root.

Service Ticket Validation: Verify legitimate use at access request time by checking a service management system.

Use logging and monitoring by connecting the PAM to an SIEM or SOC.

Addressing the Challenges of Privileged Accounts

As established, there is a strong business driver to implement PAM. However, not every organization needs a costly solution. As long as an organization can cope with manual procedures for managing internal privileged accounts, that may be the best fit. A manual process might be something akin to the “envelope procedure,” in which the password to shared admin accounts is stored in a sealed envelope (yes, a physical envelope) that is kept inside a vault (yes, a physical vault). When an emergency arises, this envelope can be opened. This opening should be treated as a security incident resulting in password rotation and a new physical envelope.

This type of process is appropriate when only a handful of people manage the system. Even where it may be effective, beware of risks: if one of these admins is absent or leaves the organization, there will be a lot of work to mitigate the risk of any shared accounts.

Privileged Access Management Solutions

Several conditions drive a need for automation and more formal solutions:

Task Volume or Team Size: When the volume of admin tasks rises or the team size grows beyond five people requiring access, automated PAM should be considered a best practice.

Internal Policy: When an organization's information security policy explicitly addresses the risks of privileged accounts, the business may need to invest in a specific solution.

Laws and Regulation: For many companies, PAM solutions are essential for complying with regulations like the European Union’s GDPR and NIS2 directives or the United States’ HIPAA and PCI DSS regulations explicitly defining the need for privileged access control.

Complex Architecture: In complex architectures, multiple administrators and sysops manage the IT infrastructure landscape. When additional architecture landscapes exist, think of IT + OT environments, as well as hybrid on-prem + cloud and multi-national / multiple jurisdiction environments. Control is becoming a predominant theme.

Outsourced Operations: In the case of outsourced IT operations, either outsourcing the data center or having external parties manage the internal data center, insight into operations and limiting risks needs to be done, and PAM will play an important role.

Readers may also be interested in reading the Body of Knowledge article “The Business Case for IAM.”10

With a need for automated PAM processes, organizations can implement a PAM solution. These solutions provide several means for managing Privileged Accounts. These can include different approaches to privilege management and secrets management, and they support a variety of operational use cases.

Privilege Management

Approval Workflows: When a privileged account is configured with an approval workflow, a user must go through several approval phases to obtain privileged access. Depending on the type and sensitivity of the access request, this may entail approvals from managers at higher levels, security teams, or technical specialists. The PAM system maintains the record of all the requests and approvals. These steps ensure that access to privileged accounts or resources is granted only when required and only under secure conditions. In turn, this minimizes the risk of unauthorized use of privileged access.

Just-In-Time (JIT) Privilege Escalation: When privileges are assigned on a JIT basis, it means only time-bound privileged access that is automatically revoked when a predetermined time expires. This control ensures that privileged access is provided only when required and prevents users from abusing permanent standing privileges. It also minimizes the organization’s overall attack surface. Combined with MFA, Request/Approval workflows, email notifications, and ITSM Ticket validation, JIT Provisioning is a powerful control.

Privileged Identity Management: Some solutions offer a combination of on-demand access and role-based access control (RBAC) provided via an Identity Governance and Administration (IGA) solution.

Secret Management

Secrets management aims to securely store, distribute, and control access to sensitive information, such as passwords, encryption keys, API tokens, and certificates. PAM solutions often offer:

Password Vaulting: A digital password vault contains the privileged account's password. Anyone who knows how to open the vault can use the password. Whenever the password is used, the password vault will rotate the password so that the used password can no longer be used or shared.

Password Rotation: PAM systems can automatically rotate the passwords for privileged accounts “on access” (i.e., when the session ends) or based on a defined frequency like every 7, 14, 90, or n days. In some cases, it even offers disposal passwords that are valid for only a few minutes or hours.

Secrets: Secrets management ensures the secure handling of sensitive information involved in Continuous Integration (CI), Continuous Deployment (CD), and API management. PAM solutions increasingly cater to API keys, session tokens, access tokens, etc. Non-human services, such as API gateways and microservices, use these tokens.

| Secret Management for CI and CD | Secret Management for APIs |

|---|---|

| Environment Variables: CI/CD systems like Jenkins, Travis CI, or CircleCI allow developers to store sensitive information as environment variables. These secrets are encrypted and can be accessed during the pipeline execution, ensuring that they are never exposed directly in code or logs. | API Keys and Tokens: When accessing external APIs, developers often require API keys or tokens. Secrets management ensures that these keys are stored securely and are only accessible by authorized services or applications. It also enables the rotation of keys to mitigate security risks. |

| Secrets Vault: Many organizations use dedicated secrets management tools like HashiCorp Vault or AWS Secrets Manager. These tools centralize the storage of secrets, enforce access controls, and often provide features like secret rotation and auditing. CI/CD pipelines can authenticate and retrieve secrets from these vaults as needed. | OAuth and JWT: For more robust API access control, OAuth tokens and JSON Web Tokens (JWTs) are used. Secrets management ensures that the keys used to sign and verify these tokens are kept secure and rotated as necessary. |

| Temporary Credentials: For cloud-based services, CI/CD pipelines can request temporary access credentials from the cloud provider’s IAM (Identity and Access Management) services. This limits exposure and ensures that access credentials are short-lived. | Role-Based Access Control (RBAC): Secrets management can enforce RBAC for APIs, ensuring that only authorized users or applications have access to specific endpoints or resources. |

| Logging and Monitoring: API access should be closely monitored, and logs should be audited to detect any suspicious or unauthorized access attempts. |

PAM Use Cases and Architectural Choices

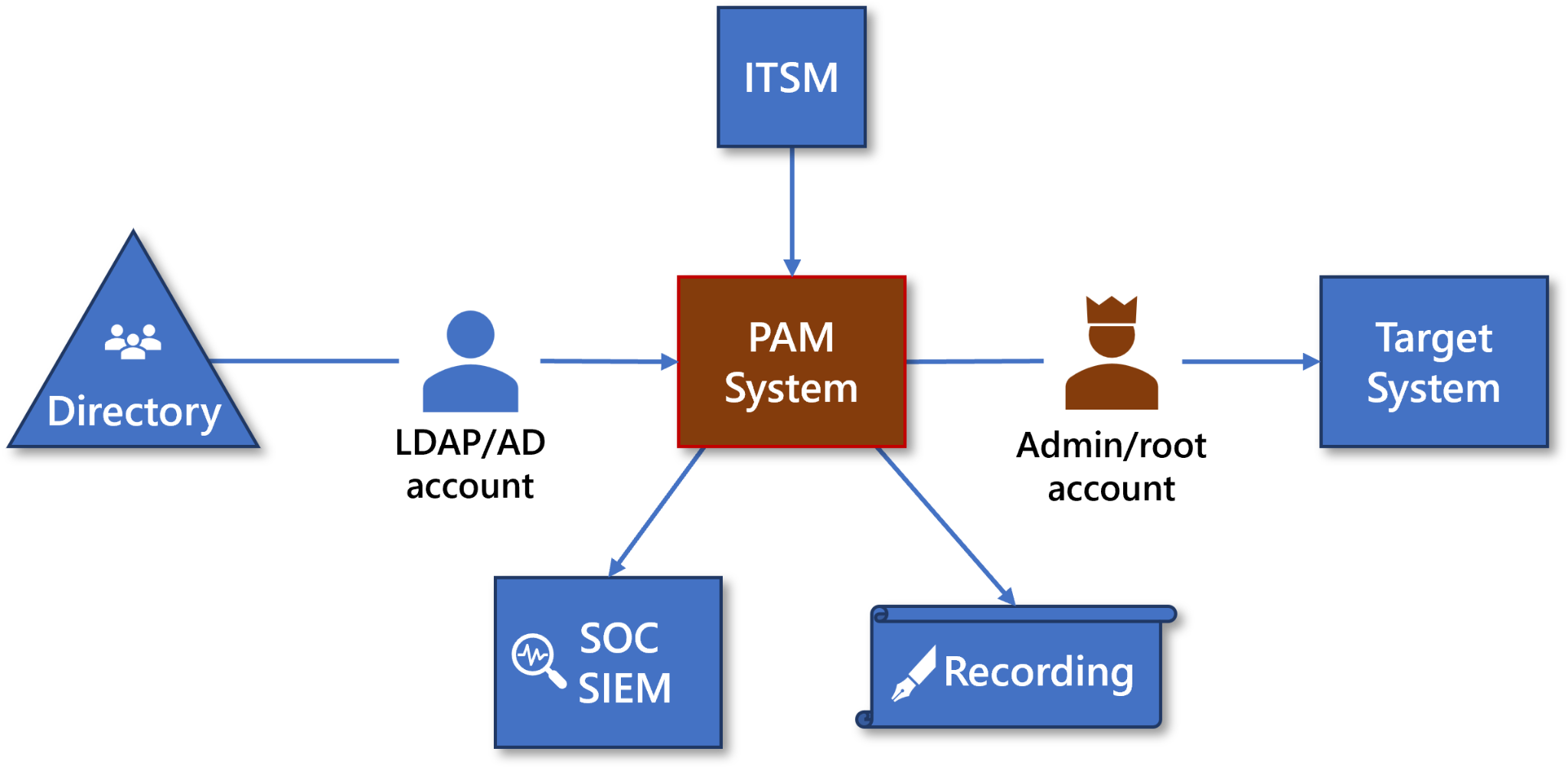

PAM as Single Sign-On: Accessing a privileged account requires a user login. When using a PAM system, the PAM system will log in on behalf of the user. For the user, this means logging into the PAM system and then single sign-on from the PAM portal. It’s not ‘true’ single sign-on since the PAM solution logs in every time, but the user no longer has to use the admin login functions.

PAM as a Stepping Stone: The stepping stone mechanism, also called Jump Server, enables a user to log in to the PAM system, and when the session is started, the PAM system gives access to secured components, like servers. Usually, this is done by creating an SSH or an RDP session that the PAM system can control (and end). It should not be possible to bypass the PAM system. Note that this approach has the added benefit of enabling remote access for target user groups.

The following section explores a variety of architectures incorporating PAM.

PAM as a Stepping Stone

Figure : PAM as a Stepping Stone Architecture

Traditionally, PAM systems are installed in a data center, close to the components they manage. PAM systems can also be implemented as a SaaS solution (see the cloud discussion section at the end of this section).

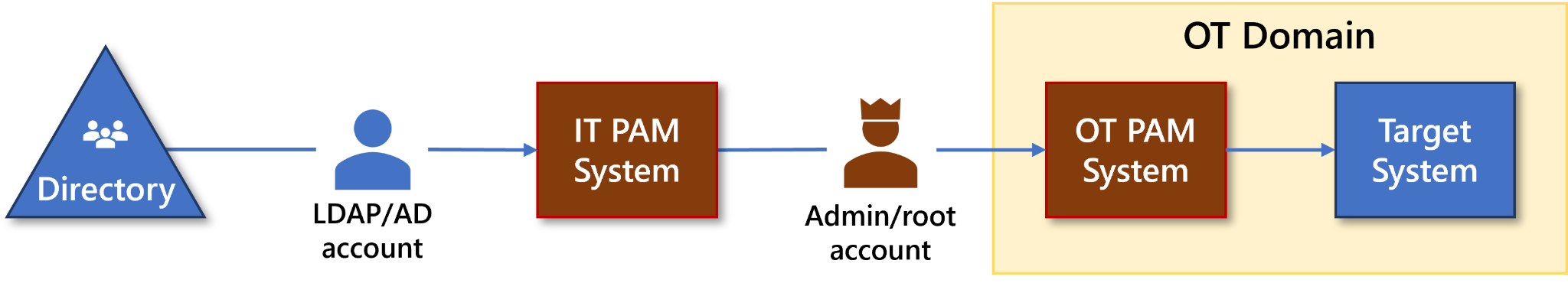

PAM in IT / OT environments

In organizations employing Operational Technology (OT) components, the IT and OT domains are separated by default. This separation may be via airgap firewalls, Industrial Control Systems (ICS), or SCADA implementations. Some organizations add IT capabilities to OT to share control center capabilities and to provide remote access and monitoring. Traditionally, the separation is done through SCADA or ICS systems. A modern and more affordable solution is to use a ‘PAM-PAM’ connection that secures access. Only through an IT-PAM system does an operator get access to an OT-PAM system, where OT tasks can be performed:

Figure : PAM-PAM Architecture in an IT/OT Environment

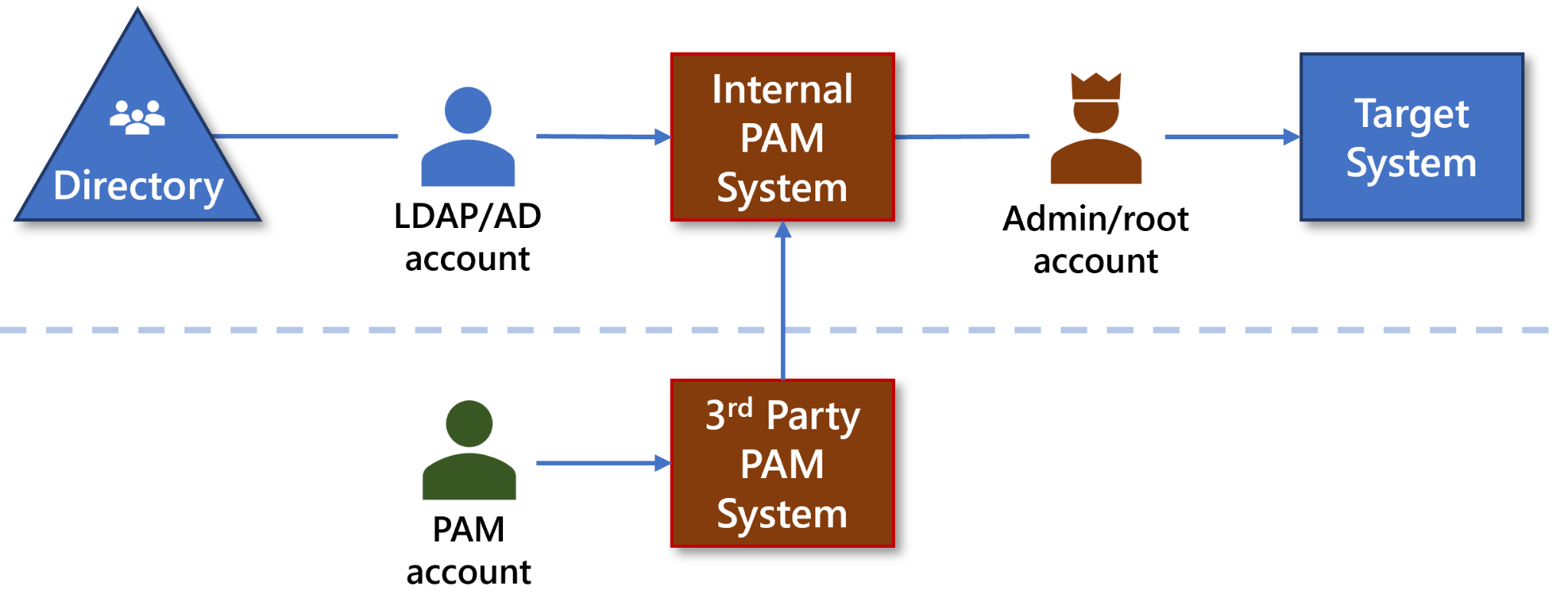

External Service Provider

Many companies outsource parts of their operations management. The component owner is accountable for granting access if a third-party manages company resources. In this case, privileged access must also be assigned to third-party operators. In addition, when using external services, the company must ensure that the service provider uses a PAM solution.

Figure : PAM in 3rd-Party Access

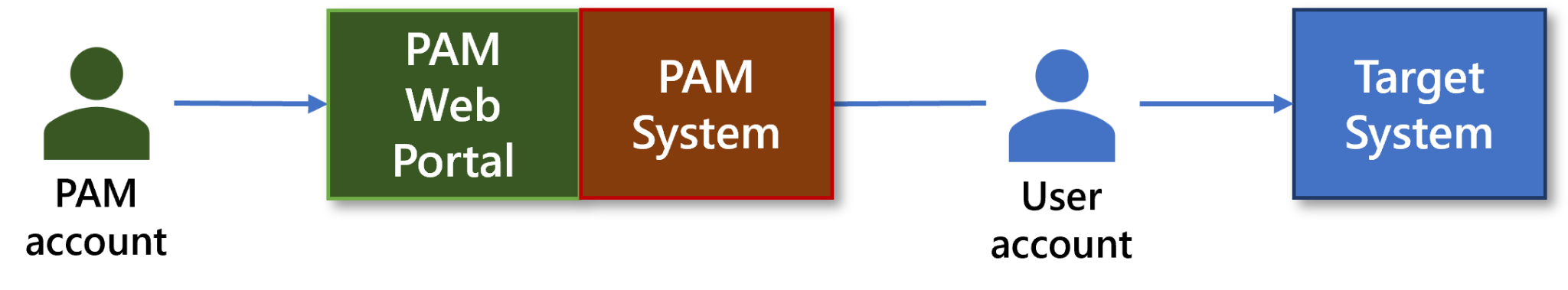

Remote access

As described above, PAM solutions can offer business users and (external) developers remote access capability. This way, legacy remote access services and VPNs can be decommissioned, resulting in lower costs and reduced technical debt.

Figure : PAM for Remote Access

Implementing PAM

Good Implementation Practices

Automated Discovery and Component Onboarding

Components that need to be managed through a PAM system must be onboarded first, meaning that the privileged accounts and passwords must be brought into the PAM system. Onboarding components can be done manually, but PAM systems can automate the discovery of components in the network to start the actual onboarding.

Session Control

Authentication and logging controls happen by default when a session starts from a PAM system. Implementors can also add risk-based session controls, such as:

Session recording: the whole session is recorded as a video-stream.

Keystroke logging: all keystrokes can be recorded to make audit or forensics possible.

Keystroke deny-list: when working in a console, specific commands can be blocked; for instance, the “rm -rf” control can be blocked, limiting the risk of destructive actions by a highly privileged user.

Beware that recording and playing back sessions should be considered a privacy and security issue. Ensure workers (counsels/unions) agree and that playback calls for 4-eyes control.11

Break-the-Glass Procedures

PAM systems act as authentication services. If the service is not available, the operator cannot get access to the component that needs to be managed. While redundancy is an essential control, break-the-glass procedures enable access to the password vault under emergency conditions.

PAM in the Cloud

Developments in PAM mirror the developments in most IT domains: where PAM systems used to be self-hosted, on-prem systems, nowadays, both SaaS and MSP options are becoming available, as well as hybrid solutions.

Third-Party Contracts

When outsourcing operations or using services provided by third parties, an organization must ensure that PAM requirements and rules apply to the third party. To protect the supply chain in this way, organizations should build this requirement into third-party contracts as well as procurement and vendor management processes.

Addressing Barriers

Adoption & Friction

PAM System adoption depends heavily on user experience. PAM systems often add extra steps to log into the target systems, introducing a new pattern. Like the reason for access, ticket number, MFA, or lack of native integration with remote tools, these changes to established methods may lead to frustration among users. This friction also might lead users to seek backdoors that help them bypass PAM systems.

Current admin account users may regret their loss of almighty powers – and may feel less empowered to manage their components. They may fear being mistrusted by management. It should be noted that these concerns are real: communication is essential in change management, and emphasis on the added functionality of PAM solutions, such as single sign-on and auditability of actions, can help.

PAM System Availability

PAM system availability is one of the biggest concerns for organizations. If the PAM system is unavailable, it prevents recovery since all the privileged accounts required to access IT assets are stored and managed by the PAM system. This risk can be countered by a flawless and tested break-glass procedure, which enables swift access recovery. Unfortunately, these break-glass accounts are often forgotten and can cause more harm than good, so it’s necessary to monitor, test, and securely store the break-glass credentials.

Password Rotation of Hard-Coded Credentials

Almost every service or application requires credentials to communicate with databases or other applications. These credentials are used to prove the application’s identity. Typically, they are privileged and embedded in various locations, such as configuration files, source code, INI files, OS services, and scheduled tasks, which are referred to as dependencies of the credentials. Therefore, when the password is rotated, the new password must also be updated in all dependencies. Many mature Privileged Access Management (PAM) systems can automatically update the new passwords in the dependencies after rotation.

Conclusion

Remember, PAM solutions do not address all risks relating to sensitive data access: practitioners must understand different privileged access scenarios and map them to the appropriate controls. First and foremost, they must consider the differences between human and non-human accounts. PAM solutions are not a panacea and do not address the thorny challenges of managing people or the non-interactive accounts that do not require humans once coded (these are demonstrably not people). Effective policy, governance, change management, and other controls are still very much required.

PAM solutions are best used for interactively used non-human accounts, although their secret management tools often cater to the needs of non-interactively used non-human accounts. Make sure that these use cases are identified correctly before introducing any technology.

Once an organization introduces PAM tools, do not underestimate the impact of culture: it can be a significant change for people. It is essential to bring people along, highlight the benefits of additional functionality, and communicate the necessity of an improved security posture for the organization.

Remember these Core Principles

Least Privilege: maximum authorization should be equal to the bare minimum required to perform a task (or simply said: “just enough” access).

Ownership: the accountable owner of a component is the owner of the non-human (built-in/admin) account. This is also true of service accounts (non-interactive). The owner of the component is accountable for providing access.

Security Controls: should be layered on top, including MFA. These must be applied with a risk-based strategy (e.g., what is the suitable retention period for session recording/keystroke logging, given the organization’s server capacity?).

Third-Party Access: with third parties, the component's owner must ensure that contracted third-party personnel only have access via PAM.

Outsourcing: The contract owner must ensure that the service provider employs a fitting PAM facility for managing the outsourced service.

Change Log

| Date | Change |

| 2024-11-29 | V2 published; Appendix added |

| 2024-03-15 | V1 published |

Appendix: A Note on Entra ID

The IDPro Body of Knowledge is an independent source of information and the authors do not endorse any specific product or vendor. With that said, we do acknowledge that guidance related to widely adopted products can be useful to practitioners.

One of these products is Microsoft’s Entra ID, formerly Azure AD. This is an Identity and Access Management solution that runs on the Azure cloud platform. It is used to manage digital identities and authorization in cloud environments using modern federation protocols like OAuth2.0, SAML, and OpenID Connect. Given its role in access control, Microsoft added extensive authorization profiles to secure access to Entra ID and Azure administrative functions. This is called “Privileged Identity Management” (PIM).

With features like just-in-time access and role-based approval workflows, one could argue that PIM is a PAM solution. This article will not weigh the benefits of PIM versus a dedicated PAM solution in general. However, when an organization works on primarily on Azure and has a compatible license,12 PIM offers a core element of its security strategy. When other platforms and on-premises systems are present, a supplementary or alternative PAM solution may make sense.

Author Bio

André Koot has over 25 years of experience in the field of IAM, and he is a principal consultant and co-founder of SonicBee, a Dutch IAM consultancy company (IDPro partner). André is focused on business consultancy and gives IAM training courses aligned with the BoK. He is also a member of the IDPro BoK committee and (co-) authored several articles in the BoK.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank BoK editor Elizabeth Garber for reviewing and helping with this article. He also wishes to thank other contributors and reviewers:

Contributors

Pranav Chugh

Sebastian Rohr

Eric Woodruff, thanks for the diagrams

Lance Peterman

Reviewers

Bertrand Carlier (IDPro)

Mike Kiser (IDPro)

Abhi Bandopadhyay

Carter, M. K., (2022) “Techniques To Approach Least Privilege”, IDPro Body of Knowledge 1(9). doi: https://doi.org/10.55621/idpro.88↩

Bago (Editor), E. & Glazer, I., (2021) “Introduction to Identity - Part 1: Admin-time (v2)”, IDPro Body of Knowledge 1(5). doi: https://doi.org/10.55621/idpro.27↩

Carter, M. K., (2022) “Techniques To Approach Least Privilege”, IDPro Body of Knowledge 1(9). doi: https://doi.org/10.55621/idpro.88↩

Bago (Editor), E. & Glazer, I., (2021) “Introduction to Identity - Part 1: Admin-time (v2)”, IDPro Body of Knowledge 1(5). doi: https://doi.org/10.55621/idpro.27↩

OWASP (2021) “OWASP Top 10: 2021,” https://owasp.org/Top10/A01_2021-Broken_Access_Control/↩

European Parliament and the Council of the European (2022) “DIRECTIVE (EU) 2022/2555 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 14 December 2022on measures for a high common level of cybersecurity across the Union, amending Regulation (EU) No 910/2014 and Directive (EU) 2018/1972,” clause 49, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32022L2555↩

BBC (2020), “Major US Twitter accounts hacked in Bitcoin scam “ https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-53425822↩

Cameron, A. & Grewe, O., (2022) “An Overview of the Digital Identity Lifecycle (v2)”, IDPro Body of Knowledge 1(7). doi: https://doi.org/10.55621/idpro.31↩

Williamson, G., Koot, A. & Lee, G., (2022) “Non-human Account Management (v4)”, IDPro Body of Knowledge 1(11). doi: https://doi.org/10.55621/idpro.52↩

Koot, A., (2023) “The Business Case for IAM”, IDPro Body of Knowledge 1(12). doi: https://doi.org/10.55621/idpro.97↩

And as a side note: storage of recordings could lead to capacity issues.↩

At the time of writing this includes Premium P2, 365 E5, or EMS (E5)↩